When people stop talking: understanding radicalisation

- Anthony Lewis

- Oct 31, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Nov 4, 2025

By Dr Anthony Lewis

In this article, Anthony reflects on how violent extremism can take hold, as it did in Northern Ireland. He warns that extremists always seek to erode hard-won democratic freedoms through censorship, intimidation and terror. Although the processes of radicalisation are well understood, they are still not being effectively disrupted. Anthony argues that the best way to counter political extremism is to reassert – rather than restrict – the principles of free speech, resisting the drift toward ever-tightening 'hate laws'. Anthony is Chair of Windsor Humanists.

Growing up in Northern Ireland taught me a great deal about political violence – and how easily any of us can be drawn into supporting extremist movements under the right conditions. As an English Catholic, I was fortunate to come from a family that bridged different traditions. We were brought up to reject absolutely the use of violence as a way of resolving deep and implacable divisions. To this day, my friendships endure across the divides that still persist despite the uneasy settlement of the Good Friday Belfast Agreement.

I had the privilege of meeting John Hume one summer’s afternoon in Donegal, over lunch, and of proudly shaking the hand of a brave and very humorous man. John Hume was a prominent Catholic politician from Derry who, throughout the madness of the Troubles, consistently rejected violence. He risked his life many times to speak with the ‘men of violence’ at the political extremes. For this remarkable bravery he was justifiably awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with David Trimble, a prominent Unionist politician. His actions demonstrated clearly that open, honest dialogue with those you oppose is the only way to secure peace and to manage our differences. My own experience in Ireland is that violence only serves to deepen division and harden our hearts against the compromises needed to achieve any lasting settlement.

Humanity’s violent nature

As Steven Pinker outlined in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), archaeological evidence indicates that humanity is, by default, an instinctively violent species. Throughout history, most states have been authoritarian, maintained by the relentless use of force and extreme violence. Authoritarianism has defined the very ebb and flow of our aggressive history, although there have been occasional brief periods of rule by so-called ‘enlightened tyrants’. All this is starkly described by Simon Sebag Montefiore in his recent comprehensive work The World: A Family History (2022), which provides a detailed account of the appalling human atrocities and genocides committed throughout history.

The historic march of civilisation has been about bringing our violent, barbaric instincts under control through the growing rule of law, economic development, and the strengthening of civil society. Human progress accelerated significantly during the Enlightenment, around 300 years ago, with the messy emergence of liberal democracies. These states evolved by explicitly eschewing the use of violence, seeking instead to resolve their differences peacefully and to manage their internal affairs through robust, open debate, democratic representation, and the peaceful transfer of power. Democracy can be seen as our collective attempt to lift ourselves out of our primeval, authoritarian past – as illustrated in the diagram below.

'Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried.…' Winston Churchill (11 November 1947)

Democracy rests upon several important pillars: free speech, freedom of information, free trade, the objective use of reason and evidence, human rights, equality before the law, and the fundamental principle of loser’s consent – without which no democracy can function. Together, these serve as the bedrock of democracy, preventing any slide back towards violent tyranny. No democracy is perfect, nor entirely free of violence or coercion, but they remain better than the alternatives, as Churchill observed in his famous 1947 speech (quoted above).

Violent extremism undermines democracy

Many enemies of democracy seek to erode its foundational pillars through increasingly extreme methods (see The Radicalisation Process below). The process often begins with the censorship of open debate – for example, through ‘de-platforming’ – and progresses to the restriction of opponents’ free speech by law, sometimes referred to as ‘lawfare’. This can lead to the delegitimisation of opposing opinions and the vilification of political adversaries, who by this stage are often labelled as ‘enemies’, ‘evil’, or even ‘subhuman’. What follows is frequently a campaign of targeted intimidation, defamation, and the ‘removal’ of these ‘unacceptable’ voices and organisations, sometimes escalating into industrial sabotage, riots, and civil disorder. Such actions may not cross the legal threshold for terrorism, but they can be just as corrosive to democracy. Ultimately, extremists may resort to outright terrorist attacks to achieve their political objectives and destroy democratic institutions. Through these escalating and increasingly intolerant and violent tactics, democracy can be undermined from within and eventually collapse back into anarchy and tyranny – as occurred, for example, in Weimar Germany between the World Wars, and more recently in Putin’s Russia.

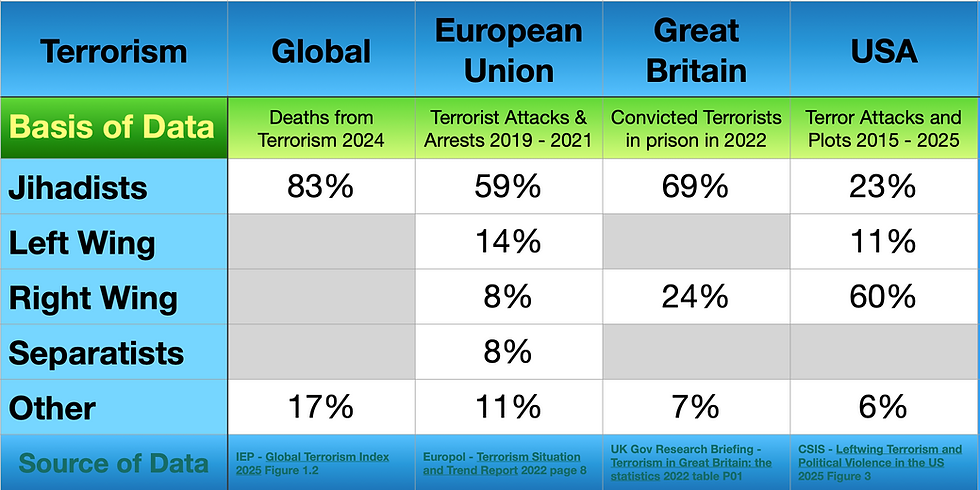

Terrorism represents the violent end point of escalating political extremism and radicalisation. The table above presents current data from various government sources on global terrorism (with links provided in the table and below). Although different jurisdictions define and record terrorist incidents in different ways, some broad observations can nonetheless be made:

Jihadist groups represent by far the biggest terrorist threat worldwide. Islamist extremists were responsible for over 83 per cent of total terror-related deaths in 2024 (IEP 2025 Global Terrorism Index). Muslims remain the main victims of these appalling atrocities, especially across the Middle East and the Sahel of North Africa, although the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023 were particularly barbaric acts targeted mainly at Israeli Jews.

The level of terrorist deaths in the West averages about 5 per cent of the global total, although this fluctuates between 0 and 10 per cent in any given year. Even so, jihadists represent the main terrorist threat. For example, in the EU, 59 per cent of attacks and arrests between 2019 and 2021 were Islamist.

Left-wing attacks and arrests are significant at 14 per cent in the EU (2019–2021). The EU also records 8 per cent of attacks as committed by ethno-national separatists, even though nearly all such groups – for example, ETA in Spain and to some extent the IRA in Ireland – were driven by revolutionary left-wing socialist ideologies.

In Great Britain, there are currently an average of about 25 terror-related attacks per year, mainly by jihadists, with peaks caused by major incidents such as the London suicide bombings in 2005 and the Manchester Arena and London Bridge attacks in 2017. Before the Good Friday Agreement, there were about 200 terrorist attacks per year, mainly by the left-wing IRA. In 2022, 69 per cent of convicted terrorists in the UK were jihadists, and 24 per cent were driven by extreme right-wing ideologies, with none designated as left-wing. Of those on MI5’s terror watchlist, 75 per cent are jihadists, 10 per cent are right-wing extremists, and 15 per cent are motivated by other ideologies.

In the United States, the extreme right wing was the main terror threat in North America from 2015 to 2025, but this threat has since fallen to almost zero following the election of President Trump. Interestingly, in the US the definition of terrorism explicitly excludes violence linked to political demonstrations, meaning the 11 per cent identified as left-wing excludes the large-scale disorder associated with the BLM riots in 2020 and the Antifa riots in 2022. Bizarrely, the more recent destruction of Tesla cars and showrooms has been classified as economic sabotage rather than terrorism. Even so, jihadist attacks still accounted for a significant 23 per cent of terror attacks and plots in the past decade.

It is clear, then, that terrorism is driven by a wide range of ideologies – including religions (currently mostly Islamist), as well as far-left and far-right political movements, regional separatists, and others – and that its nature varies regionally. However, as useful as the above data on terrorism is, it remains a lagging indicator, representing only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in measuring the extent of political extremism. By the time terrorist attacks occur within a society, there will already be significant levels of political radicalisation and intolerant militancy, both of which can seriously corrode and undermine democracy.

Understanding the radicalisation process

Following 9/11 and the terrorist attacks in Madrid in 2004 and London in 2005, Western governments have sought to develop a better understanding of how extremist ideologies and movements arise and operate, and how individuals become radicalised towards political violence and terrorism. The diagrams below provide simplified overviews of ongoing academic research and of various government models – for example, the UK’s Prevent Strategy – that have been developed in response. Together, these highlight the key aspects and stages of the radicalisation process, both at the organisational and individual level.

The extremist organisational pyramid

All political organisations or movements have a support structure that can be represented as a pyramid of increasing commitment to their cause. This simple influence pyramid is based on a generic model that is widely used in many areas of human endeavour – for example, in product marketing campaigns run by businesses, or in awareness campaigns used by charities to raise funds.

At the base of the Extremist Ideological Pyramid are the casual sympathisers – those who agree with the cause but do not support the use of violence. Above them are the movement’s supporters, who join the group as members and often endorse the use of direct action, such as demonstrations and protests. The next tier comprises activists who dedicate increasing amounts of their own time and energy to the movement. Activists, by definition, usually support direct political action, including acts of sabotage, intimidation, and disorder. The penultimate stage represents the radicals – individuals who have committed themselves entirely to the movement, often at the expense of other aspects of their lives. These are the people who devote their whole existence to achieving the movement’s objectives and who frequently lead and manage its activities and operations. At the most extreme tip of the radical stage are the fanatics, supported by the organisation or movement to carry out the most violent acts, including terrorism.

Of course, seeking to build a broad coalition of support in order to influence people and win elections is a normal part of the democratic political process. The difference with the Ideological Pyramid lies in the escalating acceptance, at each tier, of increasing levels of coercion, intimidation, and violence. In addition, extremist organisations are often tightly controlled from the top, pursuing relatively narrow objectives defined with little open debate or internal challenge, in contrast to broader and more democratic political coalitions. Most extremist organisations ‘hide in plain sight’ and often have leadership structures and founding charters that explicitly justify the use of violence and disorder to achieve their objectives. For example, in the 1980s the IRA used the slogan: ‘A united Ireland will be achieved with an Armalite in one hand and the ballot box in the other’. The original Hamas 1988 Founding Charter states that its objective is not only to destroy the state of Israel, but also depicts Jews worldwide as a religious enemy and calls on Muslims to wage jihad against them.

Building political coalitions in a democracy, and seeking to influence governments and civic policy, takes time, funding, and considerable effort. Most political proposals and campaigns will fail, or be modified, through the normal democratic processes of open debate and scrutiny – or be rejected outright if they fail to gain sufficient support. This is why loser’s consent is such an important part of any democracy: everyone must accept that, in an open and plural society, you will not get your way most of the time. The narrower a movement’s objectives, the less likely it is to succeed. This can lead to growing frustration with the democratic process, especially among the leadership and activists of such movements. As a result, those involved in more narrowly defined political causes can sometimes drift towards extremism, arguing that ‘democracy is failing’ and that the only way to achieve their aims is through coercion and violence.

We have recently witnessed a drift towards more extreme forms of direct action on both the left and the right in the UK. On the left, groups such as Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion have engaged in increasingly disruptive protests, with some of their prominent activists now serving prison sentences. On the right, movements such as Unite the Kingdom, which campaigns against current high levels of immigration, have also organised large and sometimes confrontational demonstrations.

A danger for any narrowly defined political organisation is that it can be hijacked by dedicated activists or wealthy benefactors who seek to take over the movement – either to impose more extreme methods or to redirect its objectives through ideological capture. Seizing an organisation in this way avoids the hard graft of building one from scratch and is often achieved without the support or even the awareness of existing sympathisers and supporters.

The individual radicalisation process

All of us can be radicalised to some extent – by getting involved with an extremist organisation, or through involuntary indoctrination by family, educators, or surrounding subcultures. Nowadays we can even radicalise ourselves privately at home by accessing extremist material online or being groomed remotely by extremists on social media. Becoming radicalised to the point where you are prepared to harm other people because they disagree with your beliefs or political ideals does not happen passively. It is an active process that requires significant effort and dedication. Most researchers identify four main stages of radical engagement, each showing an escalating increase in intolerance, rigidity of thought, emotional irrationality, and detachment from peaceful social norms, as illustrated below.

The first stage of the Radicalisation Process is Grievance Ideation, in which an individual perceives injustices or unfairness in society – such as poverty, mistreatment, or discrimination. They begin seeking answers to these issues through the sources of information available to them, both online and within their community. At this stage, they may engage with normal democratic processes in an attempt to bring about change. However, failure to find meaningful connection or progress in this way can often lead to feelings of alienation and psychological vulnerability.

The second stage occurs when an individual encounters and begins to engage with an extremist ideology that offers simplistic explanations and radical solutions to their concerns. This is the phase of Ideological Capture, where they are exposed to worldviews rooted in rigid, ‘black-and-white’ thinking, which blame out-groups for society’s problems and justify the use of civil disorder or violence. At this stage, they can be drawn to a cause through simplistic slogans and empty rhetoric. Of course, such slogans can also be used legitimately in democratic campaigning – for example, Obama’s “Yes we can!” or Trump’s “Kamala is for they/them.” These expressions encapsulate political ideals that, while often polarising, are transparent in intent and open to public debate. By contrast, extremist slogans such as “From the river to the sea” or “There is no debate” often carry deliberately sinister interpretations and motives, which are then cynically denied.

The individual enters the third phase, Militancy, when they fully commit to the ideas of the radical movement by actively engaging in its activities and related groups. The new ideology becomes a central part of their core identity. During this period, they often withdraw from mainstream society – even from family and friends – to dedicate themselves to the cause. They develop a self-righteous belief that their cause is uniquely moral. As a result, this is the stage at which they begin to see those who oppose them as enemies. Opponents are viewed as immoral and as legitimate targets for coercive actions such as de-platforming, cancellation, intimidation, reputational damage, dismissals, delegitimisation and abuse. The list of ad hominem tactics that can be deployed is long. As their ideological indoctrination deepens, they increasingly reject critical thinking and evidence, avoiding any rational discussion about their beliefs or methods. When challenged or held to account for their intolerant and aggressive behaviour, they often react in an irrational, emotional, and immature manner.

The fourth and final stage, Insurgency, is when the individual becomes operationally active in planning and carrying out acts of violence and terrorism. By this point they have rejected all opposing perspectives as invalid and immoral, and view dissenters as evil and ‘sub-human’. This stage represents the ultimate end point of radicalisation: they have dehumanised everyone who does not support their cause to such an extent that they regard annihilation by indiscriminate violence as justified. They may even reach the point of being willing to sacrifice themselves and to harm large numbers of fellow citizens, by planning and executing extensive sabotage, mass killings, and political assassinations.

Countering radicalisation and extremist organisations

At the moment there appears to be an increase in alienation, an erosion of social cohesion, a rise in political polarisation, and growing disillusion with democratic norms across the West – all of which are undermining our democracies. This is driven in large part by social media and by the apparent inability of successive elected governments to address their electorates’ main concerns – for example, uncontrolled illegal immigration. Our increasingly fractured politics is being deliberately exploited by extremists across the political spectrum, by autocratic states, and by global terrorist networks to further weaken our democratic foundations. These trends are alarming, because the alternative to democracy is authoritarianism. The question, then, is what can be done to protect our democracies from rising political extremism and polarisation without undermining essential democratic principles, such as free speech and the right to protest?

Most Western governments have had counter-terrorism strategies in place since 9/11. For example, the UK implemented the CONTEST Strategy in 2003 (updated in 2023), which aims to reduce the threat of terrorism through the four strands of Prevent, Pursue, Protect, and Prepare – known collectively as the ‘4 Ps’. There have been many notable successes in disrupting terrorist activity, but also significant failures – for instance, the recent ‘lone-wolf’ attack on the Manchester Synagogue on 2 October 2025. The UK relies heavily on the Prevent Strategy to interrupt the process of radicalisation, with mixed success. Given the growing radicalisation we are now witnessing, it appears that Prevent, explicitly linked as it is to counter-terrorism operations, is not sufficient to address the broader rise in political disorder. The following section outlines the minimum additional actions required to counter political extremism and protect our democracy.

Strengthen and Champion Democracy – there must be a renewed and concerted defence of the fundamental principles of democracy, such as equality before the law, freedom of speech, free assembly, and the rational, open, and critical scrutiny of all political positions. The importance of loser’s consent deserves particular attention, given that most people have never heard of it. These democratic principles should be taught across civic society, and especially in universities and schools, as part of regular citizenship education. I remain astounded at the significant effort that has gone into the widespread implementation of overtly political Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) courses across the private and public sectors, with little pushback – despite growing evidence that they are actually counterproductive. Why has there been no equivalent effort to create robust courses on democracy itself, within which DEI could be placed in its proper context? If no one in our civic society is robustly and publicly championing our democratic freedoms, this political vacuum will inevitably be filled by those on the extremes.

Disrupt the Individual Radicalisation Process — to counter radicalisation effectively, it is essential that everyone understands how any of us can be lured into supporting extreme political ideas. That is why the stages of radicalisation should be much more widely publicised than they are at present. In this way, people can recognise the warning signs, self-regulate, and call out extremist behaviour when they see it.

In the UK, the Prevent Strategy has not been adequately explained or publicised, largely because it sits within the broader CONTEST counter-terrorism framework, which by necessity operates mostly out of public view. As a result, the Prevent approach has been allowed to be undermined. It is therefore vital that Prevent is supported by a broader, more open, and independent Anti-Radicalisation initiative that can be transparently promoted and explained.

Understanding of the radicalisation process should be taught in schools and civil institutions as an integral part of citizenship education. The central role of civil debate – as the best way to resolve differences and find common ground – should be emphasised as a core democratic value. The unacceptability of political violence, incitement, and intimidation should be clearly and repeatedly stated. This effort might also include raising awareness of the radicalisation process across all communities through open dialogue sessions, especially in places of worship.

Reinforce Free Speech Protections — the philosopher John Stuart Mill emphasised the pivotal importance of free speech in challenging bad ideas and strengthening good ones. Most extremist organisations resort to intimidation and violence because their ideas are too weak to withstand critical scrutiny and can never gain the level of democratic support required for implementation. This is why free speech is usually the first target of political extremists and activists.

In recent years, the line between legitimate protest and intimidation has been deliberately blurred, as campaign groups from across the political spectrum have become more adept at building their support pyramids and orchestrating direct-action campaigns. Social media has also eroded the boundary between public and private life, normalising the targeting of individuals for harassment and intimidation. For example: is it legitimate to protest outside a public figure’s family home? Is standing directly outside the entrance to an abortion clinic an act of intimidation? Is it reasonable to get someone sacked for expressing disagreement online?

While legislation can be used to counter such tactics, poorly designed laws can easily become counterproductive, undermining our fundamental democratic rights and liberties. A striking example is the chilling effect on free speech caused by the Kafkaesque practice of UK police recording ‘non-crime hate incidents’. All these forms of intolerance – including de-platforming, cancellation, and the policing of so-called ‘hate speech’ — erode free expression and therefore weaken democracy.

The best way to counter extremist ideologies and organisations is to expose their ideas and methods to open debate and critical scrutiny. Rather than eroding free speech through ill-advised ‘hate speech’ laws, shouldn’t we be strengthening our free speech protections? Free speech is absolutely central to disrupting the radicalisation process and discrediting the justifications extremists use for sabotage, violence, and intimidation.

Final words

In the end, the only long-term and truly effective way to counter extremism and radicalisation is for all of us to challenge it openly whenever we encounter it in our day-to-day lives. For this to happen, there must be a shared understanding of how vital democracy and free speech are to our common life. Implementing the measures outlined above should help foster an environment in which open debate and civil dialogue can flourish. In this way, the extremists’ tactics of dehumanisation can be exposed and confronted.

As John Hume demonstrated in Ireland, challenging political extremism requires both the public rejection of extremist ideology and the courage to engage directly with its adherents – to influence them towards more peaceful politics, so that they may eventually be persuaded to replace their bombs and guns with the ballot box.

'When people stop talking, that’s when you get violence.' Charlie Kirk

I’ll end with a final challenge. If you thought, even for a moment, that the recent murder of right-wing commentator Charlie Kirk in the United States was in any way justified because of his politics, you have been radicalised – perhaps in more ways than you realise or are willing to admit. Utah’s Governor, Spencer Cox, put it best when he quoted Charlie Kirk in his eulogy: ‘When people stop talking, that’s when you get violence.’ He concluded that, in our democracies, we need to find a way ‘to disagree better’. As a humanist who grew up in Northern Ireland, I find myself agreeing with both their sentiments – despite our obvious political differences.

Useful links

World in Data - Terrorism

MI5 UK Government - Countering Terrorism

Europol - Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2022

UK Government Contest Strategy 2023 and Prevent Strategy 2011

Research Briefing House of Commons - Terrorism in Great Britain: the statistics 2022

The Atlantic - Left-Wing Terrorism is on the Rise - D Byman & R McCabe 2025

Centre for Strategic & International Studies - Leftwing Terrorism and Political Violence in the US 2025

CIDOB Barcelona Centre for International Affairs - What Does Radicalisation Look Like? 2016

IEP Institute for Economics and Peace - Global Terrorism Index 2025

Security Risk and Mitigation Consultants - Historical Overview of Terrorism in the UK 1970 to 2025

Thank you, Anthony. From what Mohammed put into the Koran, Islam is as brutal as Soviet and Chinese communism, Nazism and what was briefly Pol Pot-ism.

I suppose most of us are “radicalised” by our own family and social cultures. We are just unaware of it. My Victorian (born 1890) maternal grandfather took the place of my absent father, and his very outdated views entered my mind and stayed there, well beyond my leaving school. Even now, I find myself thinking as he thought.

Apart from languages and religions, political parties are another great divider of societies. I’d get rid of them, and make every parliamentary and local council candidate an independent. They would still be self-promoting amateurs.…

What Churchill saw as ‘democracy’ in 1947 – and how it is seen today – is nothing but ‘elective oligarchy’. A tiny minority ruling the lives of a great majority.

We see that in the UK today. 650 MPs (plus over 700 members of the House of Lords) together with thousands of local councillors control the lives of the 70 million inhabitants of the UK.

That falsehood has been seen through over the past few years. Hence the proliferation of protesting marches, the large increase in the vote for the Reform party, and general antagonism towards rule from Westminster.

Once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it is hard to put it back in again.

As for “Following 9/11…